|

|

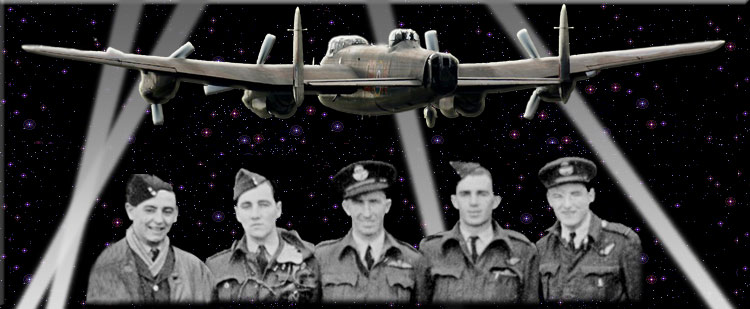

Unfortunately, there is only one known photograph

of Ernie and his air-crew, with 3 air-crew members absent from

the collage above. The RAF serviceman

on the left is a ground crew member and his name is unknown.

The full air-crew

compliment is listed below, however the name of the air-crew member

on the right is not known.

Ernie is in the centre with Flight Engineer,

Sgt CT Baker to his right, and Flight Sergeant BP Bennett

to his left. It is

believed that the air-crew member on the extreme right, with the

officer's cap,

is almost certainly the aircraft's navigator, Flying Officer F. Chappell.

It is worthy of note that all Ernie's combat

missions were carried out at night.

|

|

Pilot: |

Flying Officer

EA Fayle,

RAAF |

|

|

Flight

Engineer: |

Sergeant CT Baker, RAF |

|

|

Navigator: |

Flying Officer F Chappell, RAF |

| |

Bomb Aimer: |

Sergeant LK Topham, RAF |

|

Wireless Operator: |

Sergeant RJ Farrell, RAF |

|

MU Gunner: |

Sergeant ALN Vickery, RAF |

|

Rear Gunner: |

Flight Sergeant BP Bennett, RAAF |

|

Most

of the operational information contained in this biography has been

obtained from the Internet with the main

source being the “467 - 463 Squadrons” Website created by Peter

Johnson of Caboolture, Qld.

(http://www.467463raafsquadrons.com/). I am especially indebted to

Peter and congratulate him on his

magnificent achievement in archiving this priceless RAAF history.

Peter has travelled to England on more

than one occasion to gather information and, as just part of this

work, he has personally photographed every

one of the 1,866 pages of the RAF Operations Record Books relevant

to RAAF 467 and RAAF 463 Squadrons.

Acknowledgment is also given for the work undertaken by the late

H.M. [Nobby] Blundell in gathering and archiving information about

RAAF No.467 and No.463 Squadrons.

The transcribed ‘de-briefing’ notes in this biography may be

validated by reference to the accompanying

photographs from the official RAF ‘Operations Record Books’. Cross

referencing has enabled validation of

other material and the source of such material accompanies each

article.

The following two extracts refer to the fateful raid on Leipzig on

the night of the 19 th

February 1944. These items are

contributions to the BBC’s online archive[1]

and were made in recent years by former aircrew

of Bomber Command Lancasters although it is believed that

neither were members of 467 or 463 RAAF

Squadrons.

The first item was contributed by Sgt Alan Morgan (Flight Engineer,

Lancaster JB 421):

“.... .... .... .... If the previous raid had been relatively quiet

for the squadron then the Leipzig trip proved to be

quite the opposite. Again Bomber Command put up over 800

aircraft, but this time, as they crossed the

Dutch coast, the German night-fighters were waiting, and a

running battle ensued all the way to the target.

Erroneous wind forecasts had many aircraft reaching the

target area too early: W/C Adams (J8466) had to

orbit three times and Lt. Stevens (ND 474) twice. S/L Miller

(JB 314) returned early in Q-Queenie with

generator problems but on landing gave the following report: “Sky

above the North Sea was filled with a/c

flying in all directions -- some wiser ones with navigation lights

on, most without -- three a/c seen to explode

in air, probably due to collision.”

(It

was obvious to this observer that “see and be seen” was the

preferred option.)

The second item was contributed by Brian Soper:

“On 19/02/44 we were routed to Leipzig. On this raid we took an

additional pilot, a ‘2nd Dicky’ trip, a first

raid for a new pilot. This was supposed to be unlucky — but

we made it. I believe this was also a diversion

raid: we were meant to distract the night fighters to Leipzig

while the main force went to Berlin. There was

10/10s full cloud which was very thin, but both ground and

sky markers were visible. The duration of this

trip was about 7 ¾ hours. The following night it was

Stuttgart, quite a standard raid with ground markers.”

Airframe Ice Accretion presented a serious problem to Bomber Command

as it was a common operational requirement

to fly in low and mid-level cloud, an environment where ice

accretion can occur. The cruising

altitudes of modern aircraft are generally above these levels and

consequently the potential is far less

prevalent to-day. Also, aircraft are now better equipped should the

problem be encountered at lower levels.

Ice Accretion can affect aircraft in two ways - (i) Air Frame &

Propeller Icing and (ii) Carburettor Icing.

Piston engines have either a fuel induction system based on

the carburettor or use a form of direct fuel

injection. Aircraft piston engines fitted with carburettors

are prone to ice accretion in the venturi (air intake)

and if this does occur it causes a substantial reduction in

power with the risk of complete engine failure if the

problem is not properly addressed. The Rolls Royce Merlin

engines fitted to Lancasters had carburetted fuel

induction systems up till 1943 when fuel injection systems

were introduced. Prior to this change, carburettor

icing presented a real hazard despite measures to address the

problem being available (‘carby heat’).

Air-frame icing occurs when sub-zero temperature water droplets

freeze on impact with airframe and

propeller components - (‘super-cooled’ droplets at altitude remain

in liquid form at temps below zero and

solidify on impact). Ice can build rapidly and has the potential to

distort the aerodynamic design and

efficiency to such an extent that the safety of the aircraft can be

seriously jeopardised. Many bombers had to

jettison their bomb load if encountering severe icing conditions

because of an inability to maintain height.

Glycol mixtures were used to combat ice accretion on the

windscreen and bomb aimer’s dome. Airframe

icing occurs only when flying in cloud but Carburettor ice may form

at any time.

_____________________

Footnote

1.

WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories

contributed by members of the public and gathered by

the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar.

Click

here to return to place in text. |

![]()

![]()